On May 8th, 1945, five years before I was born, the armed conflict known as World War II ended in Europe. But the Second World War was not over then. No, I’m not referring to the Nazi capitulation a day later to the Soviets. Neither do I mean the Japanese capitulation in September 1945. In my family WWII was a part of my childhood in the 1950s.

Like almost all men of my parents’ generation, my father had served in the US Army from March 1943 until October 1944. During his training as a lineman in the signal corps he was injured when the telephone pole he was climbing split. Dad fell backwards to the ground and injured his shoulder. Because of his injury, Dad was not shipped out to Europe with the rest of his unit. Most of these men were either killed in the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944/January 1945 or were taken captive.

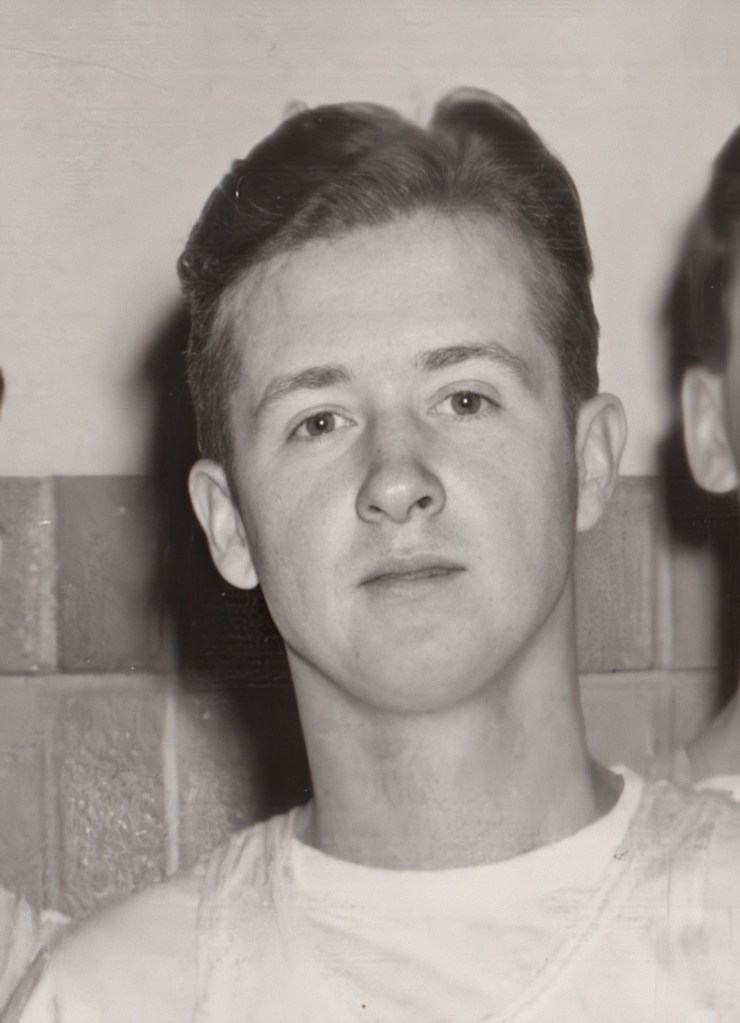

I heard this “war story” at an early age. As long as I can remember, what my Dad “did” in the war has been part of his identity for me. I remember proudly wearing Dad’s dog tags when I was about four years old.

Looking at pictures of my Dad in the family photo album was like reading an adventure story. And because Dad had been part of a photo shooting at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, I had lots of pictures of him and other soldiers to look at.

World War II was fought over and over on television in the 1950s through documentary series like “Victory at Sea”. Can I remember watching the original broadcasts that ran when I was two and three years old? Perhaps not. But I certainly saw many re-runs of “Victory at Sea” and other documentary films on TV as a child.

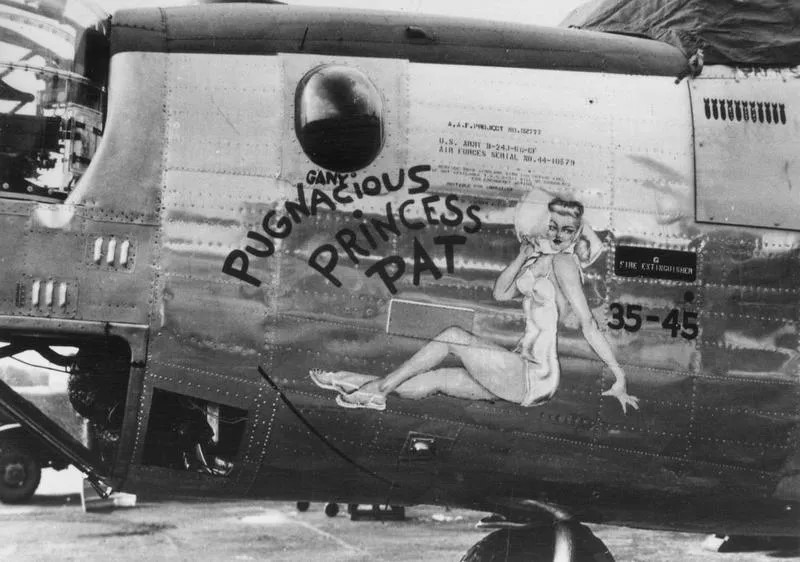

Uncle Al Dexter, husband of mother’s sister Pat Banning Dexter, had been a bomber pilot stationed in England. He liked to talk about his “Liberator” bomber which he had named “Pugnacious Princess Pat” in honor of his wife and his 35 “successful” bombing runs over German cities in 1944. Originally, Al wanted to christen the new “Liberator” simply “Princess Pat.” His superiors found that name not aggressive for a bomber. So Al added the word “Pugnacious” to the name and it was approved. I must say, though, that the lady depicted on the plane hardly appears pugnacious.

But Al didn’t just talk about dropping bombs. At the Hethel air base near Norwich Al had befriended 12-year-old David Hastings. The familiar story of how their friendship began was reported in Saga Magazine in September 1992.

Al recalls: “After the greetings and preliminaries, I reached forward to lift David over the fence [around the air base where David was standing watching planes] to show him around the plane when I was stopped in my tracks by two military policemen. True they were just doing their job but they made it plain that the boy was to stay where he was.”

Al, however, was not prepared to have any of that. “As I see it,” he told the security patrol, “we have three options here. You can shoot me, though somehow, I don’t think you would do that. You can arrest me, but you would only be doing me a favour by putting a stop to me flying for a while. Or you can get your ass out of here…”

Suffice it to say that the humbled MPs chose the third option. And David, literally shaking with excitement, got a guided tour of the Liberator.

This war story has a happy ending. In 1992 David Hastings organized a trip to England for his old friend Al and his wife Princess Pat.

Uncle John Mangan, husband of mother’s sister Margret Banning Mangan, served in the Pacific and was on the USS Callaway during WWII when it was attacked by Japanese suicide planes. Uncle John and Auntie Marge had a large book with pictures from the European and Pacific theaters of war printed just after the war. I don’t know how many times I looked at all the pictures. The fighting had ended, the pictures produced no sound of battle, but the war was present.

The war was extremely present when Uncle John told the story about his ship being attacked by Japanese planes. He related how his best friend had been wounded in the attack and then died in his arms. Then John just cried.

“Now I lay me down to sleep,” I prayed in bed as a child. At the end of the familiar children’s bedtime prayer I added the words, “And God, don’t let there be a war.” It was a fervent prayer!

Although we are only two years apart in age, I grew up with essentially no awareness of World War II until my adolescence. My father was born in November 1926 so he wasn’t eighteen until November 1944 and didn’t enlist until early 1945 when the war was almost over. He served stateside in the Navy in some kind of intelligence unit (he never seemed interested in talking about it). My closest uncle was born in 1911 and didn’t serve at all—I think he had some medical excuse? Again, we never talked about it. My other uncle, whom we only saw once or twice a year, did serve in the Army Air Force overseas, and it clearly had an impact on him, but since I rarely saw him (and it was never a topic of conversation when we did), I really knew nothing about his experiences.

I do remember neighborhood kids asking each other, “What did your father do during the war?” But I had little or nothing to add to that conversation. I vaguely recall once asking my father, and he seemed annoyed. I think he thought that men talking about their wartime experiences with their children was somehow wrong—either a form of macho boasting or a way of promoting the idea that war was glorious.

LikeLike